Global Bass talks with Master Luthier, Vadim Rubtsov

Global Bass Online. December 2000

About a year ago, I had the opportunity to interview bassist Orin Isaacs for the very first issue of Global Bass. Orin is the bassist & bandleader for the Canadian award winning comedy talk show Open Mike with Mike Bullard.

Orin Issacs playing his six string VADIM (looks like it might rain!) on the OPEN MIKE with Mike Bullard set,

and standing with Victor Wooten, a guest of Orin’s on the show.

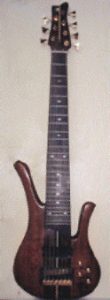

Now it has been addressed in previous issues of Global Bass, the search we all are on in the pursuit of the Perfect Bass. Few of us can pass a music store without going in, and once inside we all succumb to the dizzying rush upon seeing row upon row of bass guitars.I was aware of the fact that he used a type of both five and six string bass that I had not seen before. Near the end of the interview, I asked him some information about the basses and he promptly got up from his seat and went to his dressing room closet. He brought out a soft-shell case that held two of them. Sliding the 6 string from the case, I immediately recognized it as the one he uses predominantly on the television show.

More often than not however, you leave the store feeling vaguely unsatisfied. Often these shops are safely stocked with all the standards, brought into the store because they are guaranteed to be easy sells, so it is seldom if ever you come across a truly unique instrument. An instrument so individual that calls out to you alone, one that feels so perfect in your hands, it is as if it were made for specifically for you and no other.

Such was the feeling I had as I held this beautiful 6 string in my hands. The woods were a wonderful combination of both light and dark, the neck-through was connected to the wings of the bass perfectly. Not a single smear of the lacquer marred the finish, the personality and the essence of the woods had been lovingly matched, sanded, polished and brought to the point that it felt as if they were alive in my hands. The neck, though wide enough to accommodate the 6 strings, still was so thin from front to back as to cup your hand. It was a breeze to cover the normally intimidating expanse of 6 strings.

The volume and tone pots were recessed and angled up to you so you could see where they were set. The body was so thin and so light and perfectly balanced it felt more like a four string than the monster that it was. The back of the bass was contoured inwards to fit your body. The control panel cover that held the volume and tone pots was made from the same wood as the body, allowing the lines and the statement of the wood’s grain to flow uninterrupted.

This was more than an instrument, it was a piece of art.

I have been looking for The One for over 30 years, The Instrument that truly was built for me…and it seemed as though I had finally found that bass! The only problem was this wasn’t mine, nor would it ever be. Needless to say, I was quick to ask Orin who the luthier was that had created such a masterpiece.

I was very pleased (and relieved) to find out that in fact the man who had built this and all of Orins basses for the show was a Russian immigrant now living in Canada in a town not 50 miles from where I lived. His name was Vadim.

However, once back home after the interview with Orin, I got caught up in the production of this magazine and had let time slip away, not really forgetting about the basses (how could I?), but just not able to really get the time to pursue them.I knew at that point that I had to interview him for the magazine, not only for the benefit of our readers, but also to gather a bit more information about these wonderful instruments for myself. I figured that if they caught my attention so completely, it was likely they might for others as well.

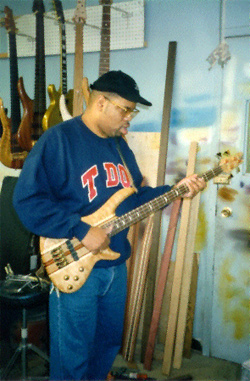

One day nearly a year later, the phone rings, and a quiet voice with a strong European accent introduces himself as Vadim and he says that he has heard that I would like to talk to him about his basses. Needless to say, within two weeks I am sitting in his workroom in an industrial mall in Toronto. We are surrounded by half finished instruments, tools, dust, the distinct smell of lacquer and paints, with the walls covered in a riot of different colors where he has used them as a test board before painting his instruments.

In the midst of all this sits Vadim, a man in his late 40’s, thin and with thinning hair, somehow not the eccentric I had expected. In my imagination I had built some sort of image of an Einsteinian individual, hair is disarray, speaking loudly in short emphatic sentences. Instead we have a quiet, reserved man, proper and well mannered.

This images slowly adjusted however as the interview progresses, and soon I realize I am in the company of someone who views his work as his life’s mission, someone who has fought very hard for it. Haunted by a romance between himself and his drive to find the perfect musical instrument hidden within mere pieces wood.

Humble Beginnings

In the quest to understand this man, I ask him where this journey started and what set him upon the path of building in the first place. He said he began at the age of twelve in Odessa, in Russia and I asked him what had got him actually started.

Vadim: Well, everybody was crazy about The Beatles and don’t forget we were living in a closed society. Everything was done Underground, everything was banned. The music that was allowed was all official, art was official and all controlled by the KGB.

Art, literature and music was allowed if it fit the purposes of propaganda. It was a fascist society, everything was controlled. They thought that everything that was away from that was coming from evil, from the Capitalists.

They should have built a statue of The Beatles, because in my opinion The Beatles helped destroy Communism. It started with their music, because all that music was restricted, and then we started to listen to The Voice of America (radio station), the BBC and other stations, just to find more and more news about Rock `n Roll.

This was because there was nothing else there. Any real information came from outside sources. Those stations were working against the Communists. They would throw ideas into your mind, mixed along with The Beatles. They would say So here are The Beatles, and right now somewhere in the Ural Mountains there is also a devastating crash at a nuclear plant, that nobody knows about. Or they would say “Today they put such and such a dissident in the prison, and here are The Beatles. So after 10 years of that kind of thing nobody believed the crap of the official radio or television of the Soviet Union.

Over there, there were a lot of creative and intellectual people. My mother was a poor Classical musician, teaching University, she was also an Art critic, she taught music theory and the history of art and music. She knew 5 languages, but that didn’t pay the bills. It’s sad, but that was how we lived.

At our house, sometimes there was nothing in the fridge, nothing, but there was a bottle of Vodka on the table, and the kitchen was full of her friends: artists, poets, KGB informers, (because they were always around the Bohemian people) and musicians.

Building Something From Nothing

So at the age of 12 I was playing piano. I hated it, because it was my mother who was teaching me and she taught with a really heavy hand. She could slap really hard! (He laughs) I did the piano lessons but at the same time I was crazy about The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

I loved the bass. But there was nothing to play. No electric guitars, no amplifiers, no speakers, nothing. If you can image the whole entire city, 1 million people, but all the telephone booths had all the headsets cut off! We were stealing them to make pickups. Cutting the telephone headset to get the magnets and the wires to build a pickup. You cut the telephone and you could get in trouble with the Police. They wouldn’t say anything, they would just beat the crap out of you.

I loved the bass. But there was nothing to play. No electric guitars, no amplifiers, no speakers, nothing. If you can image the whole entire city, 1 million people, but all the telephone booths had all the headsets cut off! We were stealing them to make pickups. Cutting the telephone headset to get the magnets and the wires to build a pickup. You cut the telephone and you could get in trouble with the Police. They wouldn’t say anything, they would just beat the crap out of you.

So the first bass I built, you could call it a ‘neck-through’ because I build it from a piece of 2-inch pineboard that I had picked up. I didn’t know anything about it, I just wanted to play the bass. I got it from a construction site, it was raw and the guys there just ran it through a planer.

It was -30 degrees there, the middle of winter and I dragged that board to my house. I started saving my money, money which my mom was giving me for lunch. For 20 cents, you could have a small dinner at school. No, the 20 cents went towards the scroll blades. This was because I didn’t know how to cut the wood. I drew the picture of the violin bass (The Hofner Beatle Bass), and for three months, every day I was cutting and using approximately a pack and a half just to make a move of four inches on that two inch thick board. When I cut it, I cut the whole profile, neck and body. It warped, so it became the shape of a Warwick (laughs).

No truss rods, I knew nothing about truss rods. I drew the fingerboard and measured up the frets from a popular magazine of the time. They called the magazine The Modelist Constructor. For all kids who make models of planes, trains, ships, and it was good magazine. There were a couple of guys building guitars at that time. The first pre-amps were there too. They said to boost the signal out of a small pickup you had to have that pre-amp. I remember the schematic. One transistor, a couple of capacitors and a couple of resistors. That’s a pre-amp with what they called a 2 Band EQ.

They also gave the idea on how to calculate the frets. But there was nothing to use for frets.

GB: So what did you use?

Vadim: Nails. You take a nail, you make it into a C-shape on the vise, then you bang it with a hammer and keep working it with files to make it square. Then you bang the sharp edge into the wood. It worked. Machine heads, no machine heads for bass. What do you do? You used guitar machine heads.

GB: But they were never built for that kind of tension!

Vadim: No, and they broke, so you replaced them with another one.

GB: What did you use for strings?

Vadim: You just go to the nearby musical college with cutters in the pocket. You just watch the poor guy in the corner who is practicing his upright bass. The bass belongs to the college, so they will replace the strings.

You just watch him until he takes a break and as soon as he leaves, you go in and cut the strings, wrap them in a circle and run away! We also stole strings from pianos. The school, we were so crazy about building the bass, we just watch the piano player, he leaves, you just go in, cut it from the bottom, cut it at the top, but they were so heavy! But now you had flat-wound strings!

Speakers? Anywhere you could find a broken radio, five-inch speakers, whatever you can find. You just build a box, and you put 15 to 20 of these speakers in. You blew them, but a least you could produce some sound. Boom, boom, boom, then that’s it, it’s gone!

I played that bass from 1968 until about 1974. We played CCR and Deep Purple. I came back from the army in 1977, we all had to join the army. The music had changed, Rock wasn’t too popular. In Odessa what was really popular was Funk. Bands like Parliament, Wild Cherry, Herbie Hancock, Jeff Beck, Earth Wind and Fire, George Duke, Stanley Clarke.

In 1977-78 slap music, funk music came to Odessa. You can’t play slap on round wound strings, you can’t play slap on a Hofner Bass, so you need something different.

There was one Jazz Bass in the whole city! It was a Jewish guy whose relatives from Brooklyn sent him a Fender Jazz. He never played it in the restaurant, like most musicians played in restaurants, people went there for dining and dancing. He never played it in those restaurants, he kept it in a case in the house.

He allowed me to take the measurements from that bass, tracing it completely. He did this so that I could build him a fretless and that is when I started building Fender copies. From 1977 till 1981, I was satisfying people in Odessa building Fender copies.

By that time there was in the Underground, guys who were building copies of Precision and Jazz pickups. They realized there was a market there, for machine heads as well. The guys in the machine shops were making those. You could find supplies.

I really like that guy (the Jewish man) because he taught me to pay attention to small details. We just didn’t have Fender screws there, we had screws with a flat head. I put those flat heads in there and he said ‘No’. So you took every screw out and started filing it to give it the round shape. And then you had to bring it to the guy who put the chrome on it.

GB: So that helps you now in paying attention to the small things?

Vadim: Probably. Because he said to me ‘Look at this bass! This has to be exactly that size and this has to be placed right here!’

We’ve Gotta Get Out of This Place!

Vadim explained that the man taught him things about the body design as well. Knowledge such as the fact that the horn on the top of the bass usually is right above the 12th fret, not only to balance the weight, but also to align the bass over the left shoulder and the line of sight.

All of these skills, this knowledge, coupled with his innate skill and talent, continued to develop and grow, but he knew that the only way he would ever be able to pursue the life he wanted to live, building the instruments he loved, meant that he would have to get out of Russia.

Vadim: The reason I came to Canada was that I would go anywhere just to get out of the Soviet Union. That actually was my goal for 10 years. Eventually I managed to get out in 1987. My wife and my son had left before me and I ended up working on the Pacific Ocean on a fishing boat. I had tried to escape (from the Soviet Union) for 4 and half years, trying to open up a visa as a fisherman so I could escape to any foreign seaport, but it didn’t work.

The KGB is the KGB. They didn’t have computers, but they did have fax machines and telephones, so they never opened visa. So my efforts were useless. For some reason they finally opened visa in 1987 and in 1989 I came to Canada after staying for a year in Italy waiting for permission to come. When I left the Soviet Union I just brought as my possessions, two unfinished basses and a bag of tools. I am still using the tools.

GB: Were you hoping to start work as a luthier in Canada right away?

Vadim: Sure, I was hoping to do it right on the spot, right from the beginning but it took more than a year and a half to two years to realize where I had to go and what I had to do. I ended up working for UPS simply as a matter of survival.

One day I just quit UPS because I met Ed McDonald (of Tundra Music in Toronto) and he encouraged me to just drop that thing and start my own thing. I had mentioned to him that I was building bass guitars. I was building them in a closet in an apartment building. He said to me, “Yeah, yeah, sure, building? Show me!” So the next time I brought an instrument, he saw it and he actually sold that instrument. He said, “You know guy, I don’t know what the hell you are doing with UPS, wasting your time. You’ve gotta start!” Since that time I’ve been building and building.

GB: The two basses you brought from Russia, where are they now?

Vadim: One I was using for a time, it was a bottom-tuning bass (like a Steinberger), as a testing device for pickups. The other one I gave away to a friend of mine in the States, it was a fretless I had finished in Italy. Then I started studying what was on the market, what’s hot, what’s not, and I started building my own stuff.

GB: This was when you ran into Ed McDonald and were offered a booth at his Vintage Guitar show? What did you use for display instruments?

Vadim: For the show I used the 10 instruments I had built in my bedroom and closet over two years.

GB: You must have been really popular with your wife!

Vadim: Well actually, my wife left me! It was a place near the corner of Jane Street and Finch (in Toronto), in a townhouse. I signed my name on it, we bought it and then we just split. She left me there, so what use was the Master bedroom? I brought all the machinery upstairs and started doing work. It was about 25 square meters, good enough. You can make noise 24 hours a day, nobody complains, because the guys outside are playing crazy Reggae, boom, boom, boom! Twenty-four hours a day.

GB: The wife now, is she the same lady, returned?

Vadim: No, she is my second wife. She is really supportive, she is not into money. She says, “If you are not rich now, you won’t be rich. The reason to do it (become rich) is that you have to love that subject we call money. You have to think about it all the time, you have to chase it like something you love and will do anything for. So relax and enjoy your life.”

GB: You are one lucky guy!

Vadim: Well first of all, she likes a creative person. She doesn’t like the guy that does the 8 to 5. She really likes what I am doing. She says, “Okay, you do this, but at the same time don’t forget where we are living, how much at least we have to spend on the apartment and this and this and this. You sell the bass? You sell the bass! You don’t sell the bass, you do something part time, whatever, to help pay the bills.”

That part time job is driving once more as a long haul driver for a trucking firm. He heads out on Monday of each week and returns Wednesday or Thursday. Once back, he throws himself back into working on his basses.

The Future?

I asked him if he had the choice would he choose to work full time building. and does he resent having to drive for a living? He says that the one thing he gathers for himself when he is out on the road is the chance to plan his next instrument and the kinds of woods and the colors he will use. In travelling recently through West Virginia, Pennsylvania and North and South Carolina, he was overwhelmed by the colors of the trees as they turned towards winter. “Those colors still stick in my mind! Greens, bluish greens, burgundy, browns through to yellow, it was unbelievable!”

When asked if at some point he found his work was so much in demand that he could move to mass production, he said…”I don’t want to produce Model One, Model Two, Model Three. I’ve been to the trade shows, the NAMM show, and I will bring, one, two, three basses, and people ask me, ‘How many can you produce a month?’. Then ‘How many models do you have?’. They want different models, a solid commitment on how many I can produce, and at what solid price.”

“Then you have a headache. Space, people, machinery you have to deal with. I don’t want to deal with that. I come here, I put the music on and nobody’s around. I don’t have to pay attention to what someone else says or control what other people do. It is really hard to find some person as crazy as you are! You’ve gotta be crazy about what you do! You’ve got to not be able to imagine what life would be without your work. It makes your life so that every day is beautiful. Sometime I see miserable people, despite their money, despite all those houses and those material things they possess, they are miserable”

Out of the Woods

GB: The woods that you use for construction, where do you get them?

Vadim: I have a couple of suppliers but I still also always keep my eyes open. I also have a friend who runs a furniture factory and sometimes they come across wood that is not suitable for their product line. I also have a guy in British Columbia who supplies me with quilted maple and spalded maple.

He shows me what at first glance just looks like a pile of wood, but as he picks up each piece, he points out qualities that the untrained eye would not see. Birdseye full of incredible swirls, coloration’s both intense and subtle. Soon what first appeared as a mere pile of wood becomes a small gold mine of opportunity.

Vadim: To some people it is dead wood, nothing. But I can already see the outcome, what I can do with it, what I can achieve with it. If I can slice this piece just here, I can pull out a book-matched piece and I can already see what I can get out of it. See this piece of walnut? It looks warped and cracked, but to me, it’s a treasure. I know what I can get out of it.

My concept is that we are part of the earth. Real musicians, real musicians, their purpose is to bring positive energy to the world. People sit, have food, have a drink, they have entertainers which bring the positive energy to the energy the food already has around the table. People when they eat exchange their positive energy. Food is part of it as well.

Well, if musicians have to conduct the positive energy, the instrument he holds in his hands, it is a conductor too. It is part of the chain. It has to be made with positive energy by whoever builds it, because it goes into the hands of the guy who conducts that positive energy to others. Wood grows on the earth, it grows with energy, it has energy.

He points to a bass on the wall and says, “See that bass with the Purpleheart, that wood is roaring!” I notice a half-completed bass on a hook and comment on some of the laminations, and how he has managed to bring out some very nice and subtle effects.

Vadim: You do it with a bit of a stain and you work with it. The stain goes into the wood and allows you to bring those markings up, it creates a three dimensional effect. I saw PRS (Paul Reed Smith) doing it and wondered how the hell they did it! So I went home and tried. Eventually I was able to produce the same result. But nobody wants to do this kind of work, so much work, in a factory.

GB: If a person came to you, told you what they wanted, worked out a design, chose the woods and the hardware, how long from then would it take before they had the bass in their hands?

Vadim: If I am here in the workshop, not doing anything else, to build it to the point of spraying it takes one week. Then another week just to spray it and of course the drying process takes a while. You have to spray, dry and then level the finish. It takes at least five coats. This way you don’t see any shrinkage of the lacquer that you see on fast production. They spray it, they polish it and out the door! Next year it has become an oil finished wood, it is not a high gloss any more.

GB: The hardware?

Vadim: For bridges, I use Hipshot. The guy is right around the corner in upstate New York, he gives me a good price and great quality. As for pickup, I have a guy in California, he builds pickups and electronics for me. He is amazing. But at the same time, it is by request, if you want Bartolini, I’ll put in Bartolini, you want EMG, I’ll put them in.

There is a guy I met at the NAMM show, his name is Ken Armstrong and sent me his pickups too. Machine heads? Gotoh…or Hipshots.

GB: What kind of guideline do you use for your pricing, considering each bass is individual to its purchaser?

Vadim: People will try to bring the prices down, down, down. I say, ‘No’. What do you expect a mechanic to charge you for an hour? At least $45. So to build these basses takes 80 hours of work. I do charge less though, I charge $2500 for the work, all the rest is whatever the customer wants (hardware etc.). If they want a five string, or a 6 string, special neck woods, it’s more. Special machine heads…Exotic woods, they are costly. Ebony fingerboard, not a problem. But for that fingerboard, I have to buy a block of ebony that will cost a $100.

The Fingerprint

Vadim said that he would likes to sit down with a client and talk with them, find out abut their likes, dislikes, what they wanted and what they didn’t want and then build a bass uniquely for that owner. Yes, his basses are boutique basses and he knows they are more costly than production models. But he doesn’t build production models, he feels his basses are as unique as a fingerprint. Production models are turned out in the hundreds of thousands and all of them are the same. To him, this is not a bad thing, but it is not the route he would like to follow.

Vadim would be happy these days just building two instruments a month, using the income from one to cover the costs of the woods and supplies and the income from the other would cover his cost of living. Then he would be at peace, happy to be a craftsman in the trade he has followed since he was 12, happy to live in a part of the world where he is free to build his instruments the way he wants and for whom he wants.

Vadim would be happy these days just building two instruments a month, using the income from one to cover the costs of the woods and supplies and the income from the other would cover his cost of living. Then he would be at peace, happy to be a craftsman in the trade he has followed since he was 12, happy to live in a part of the world where he is free to build his instruments the way he wants and for whom he wants.

GB: Has there ever come a time, when you have built an instrument that so captures what you had envisioned, that it is very hard to impossible to let it go, to actually release it to the client?

Vadim: Every time! From one point I build it for him, from another point I build it for me. That thing, that bass can become a woman. It can be a classy woman, very strict, or it can be nothing more than a street broad. A little bit garish. You visualize this, I like women! If I think about those curves, that’s like a woman’s body.

Vadim: Every time! From one point I build it for him, from another point I build it for me. That thing, that bass can become a woman. It can be a classy woman, very strict, or it can be nothing more than a street broad. A little bit garish. You visualize this, I like women! If I think about those curves, that’s like a woman’s body.

So I build it for him, he comes to the shop to see it. He sits for 20 minutes and plays. He has a serious look on his face. Two hours pass and he is still sitting there playing but there is a smile on his face. That is when I know I can give the bass over to him. That smile tells me I have done my job right.

So really it comes down to this…You have to decide whether you want to dedicate three or four thousand dollars in 3 or 4 basses, bought from a production line. All fine instruments, all covering specific areas of sound, playability, looks, each one perhaps appealing to a particular aspect of your personality.

Or the other option is to sit with a luthier such as Vadim, discuss with him what you want and what you don’t want, and have one, maybe two instruments built exactly and specifically for you. Built like an extension of and covering all aspects of your soul and your musical personality. As the Beatles used to sing, and Vadim would be quick to remind you, “Whatever gets you through the night!”

Myself, I know what I am going to do.